This may or may not surprise you, but a huge factor in the settling of the American West was all about politics. Yep. I’m not a big fan of politics myself, but you can’t deny that it sure does have shaping power. And as romantic as it is to think about the West being settled for dreams of building a better life or civilizing the wilderness or even getting rich quick, a lot of it had to do with one political party trying to out-maneuver the other.

And that’s not even taking into account the whole reason why the Oregon Trail was established in the first place. You see, in the 1830s, there were already a few trading towns in the Pacific Northwest. The purpose of these towns was to provide ports for traders to export their goods to the rest of the world. But whether those key ports would be controlled by Americans or the British in Canada was still up for grabs. Borders and boundaries were a little fuzzy that far west, and since the home office of both governments, so to speak, was so far away in the East, it was easy for both sides to proclaim their country’s borders to be wherever it was most convenient for their interests to say they were, even if they overlapped.

So who is going to win a political argument about borders in a far, far distant—and yet economically key—area? Why, the country who has the most settlers in place to lay claim to the land. One of the reasons so many Americans were encouraged to pick up everything and dash west, carving out the Oregon Trail as they went, was because the government needed as many card-carrying Americans in place on the ground as possible so that they could claim the ports. It was a unique version of “squatters rights” played out on an international political playing field.

So to make a very long and not particularly interesting story short, President James Polk brought the political and foreign policy aspect of the Oregon border dispute to a head by first threatening to go to war with Britain over it, then compromising and agreeing to mark the border at the 49th parallel in 1846. Just keep in mind that it could have gone very differently and Oregon could have ended up as part of Canada if settlers weren’t encouraged to take the Oregon Trail and make their fortunes in the new land of opportunity.

This wasn’t the only compromise with a political slant that shaped the West, though. In fact, one of the most potent forces in the rush to expand settled land in the West was a result of the good old Missouri Compromise.

James K. Polk – I had to do a project about him in 6th grade and I’ve never forgotten him since.

Courtesy of Wikkicommons

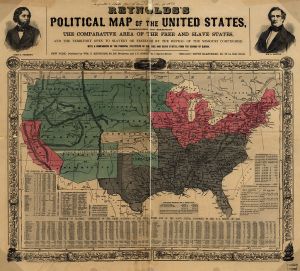

The Missouri Compromise was an act of epic political scale that is one of the first things we all learn about in high school as we study the lead-up to the Civil War. I know I never really paid much attention to it beyond what I needed to know in order to pass those history tests, but actually, it was amazingly important to the way the West was shaped in the mid-19th century. In a nutshell, the Missouri Compromise was a law passed in 1820 that prohibited any state north of Louisiana, with the exception of Missouri, to be a slave state. South of that line, you were good to own slaves. North of it? No slavery allowed.

That sounds simple enough, but in 1854, as the rumblings of war were really beginning to heat up under the surface of this country, the Kansas-Nebraska Act was passed in an attempt to negate the dictates of the Missouri Compromise. Meaning that the new states of Kansas and Nebraska could determine for themselves whether they would be slave states or free states based on a vote of the men living in those states. In other words, the population of the states could self-determine which side of the issue they would come out on.

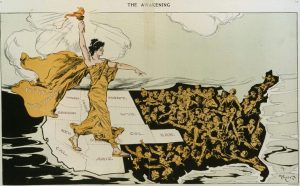

So what did people do? They rushed as many settlers out into Kansas and Nebraska as they possibly could. Both sides did it. The population of these states skyrocketed, not because they were seen as the land of opportunity or a means of getting rich quick, but because each side of a political debate back East needed as many voting men on the ground as possible to win their way.

Of course, as we all know, fighting broke out, “Bleeding Kansas” became a nightmare of a place to live, the Civil War burst out in 1860…and the population of the west rose as settlers who came for one reason stayed for another. The same is true of California and several of the other western states, by the way. Funny how populating territories can become a tool of politicians hoping to win an argument.

But in case you were worried that it was all cynical Sally, once the Civil War did break out, the population of the west began to expand again as war-weary, disillusioned segments of the populace looked for ways to escape the bitterness back east. But I’ll talk about that next time.